Clothing brands sold in New Zealand are keeping the women who make our clothes in poverty.

No matter where we live, we all deserve to live with dignity. We deserve to live in a decent shelter that doesn’t leak when it rains, to eat nutritious food every day and have enough clothes of their own. We want our children to finish their education and thrive. We want meaningful work with businesses that treat us well and pay us a living wage.

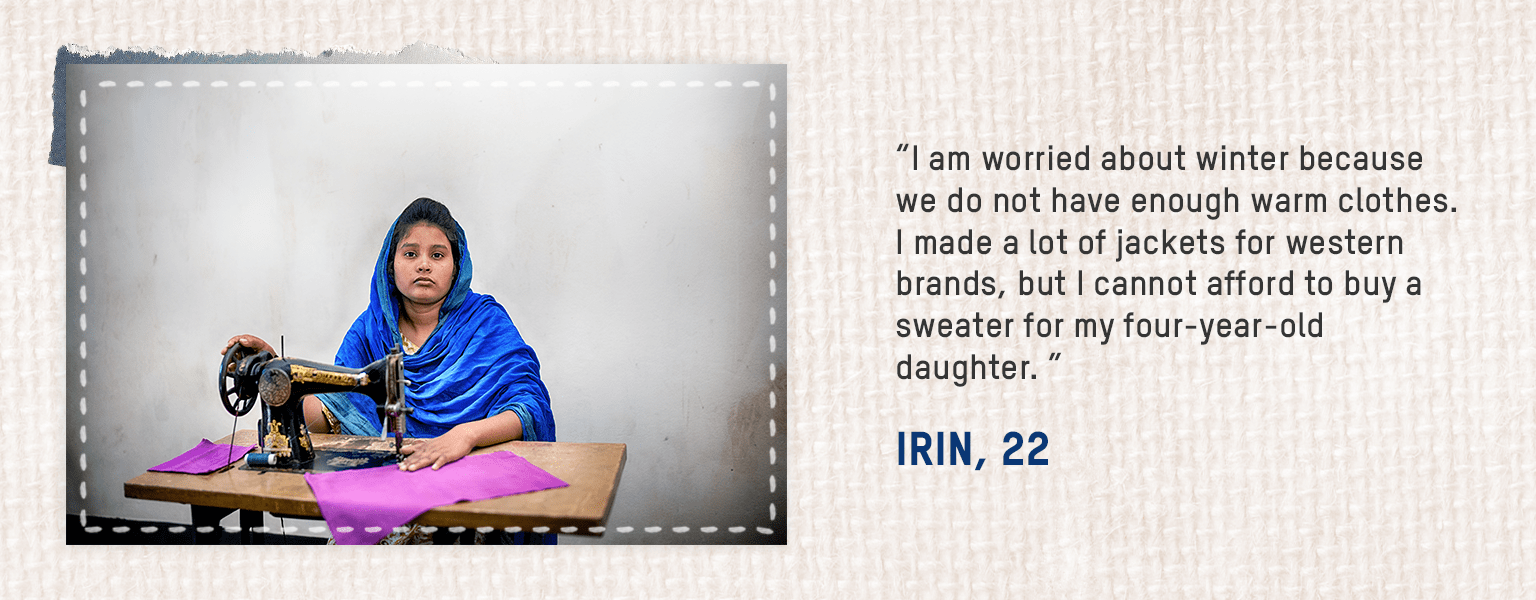

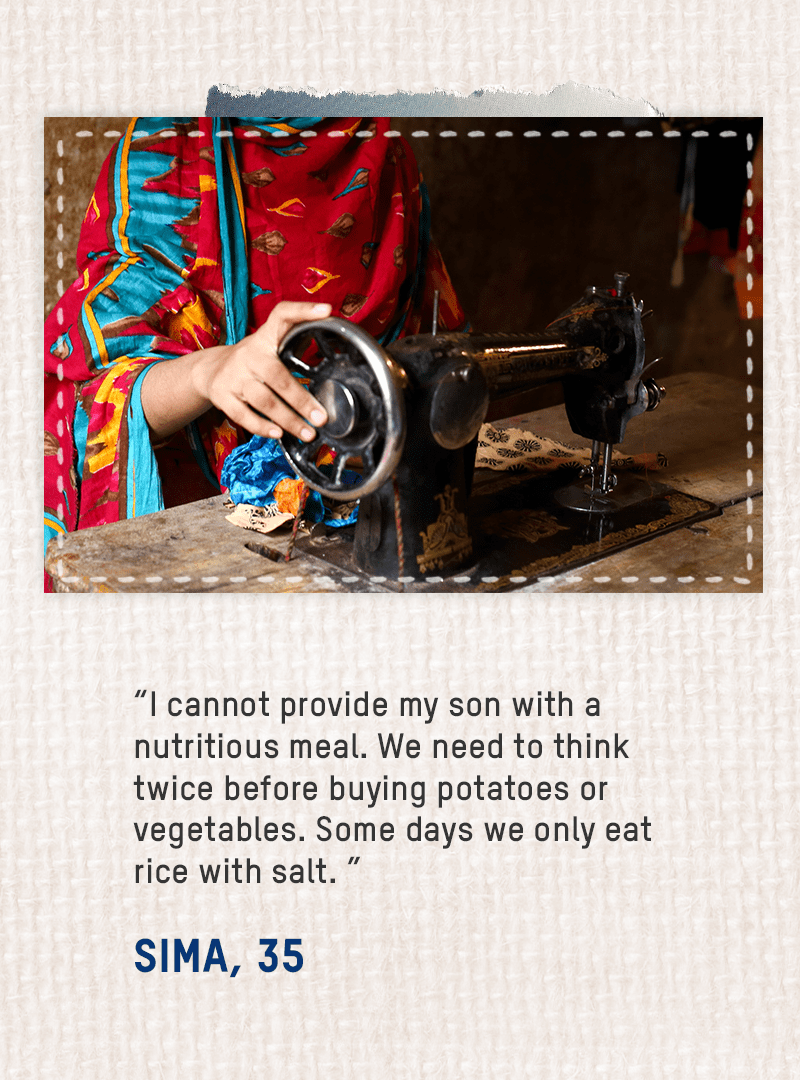

But this is not the case for the women overseas who make our clothes. Did you know that the minimum wage in some countries does not even cover the basic costs to live?

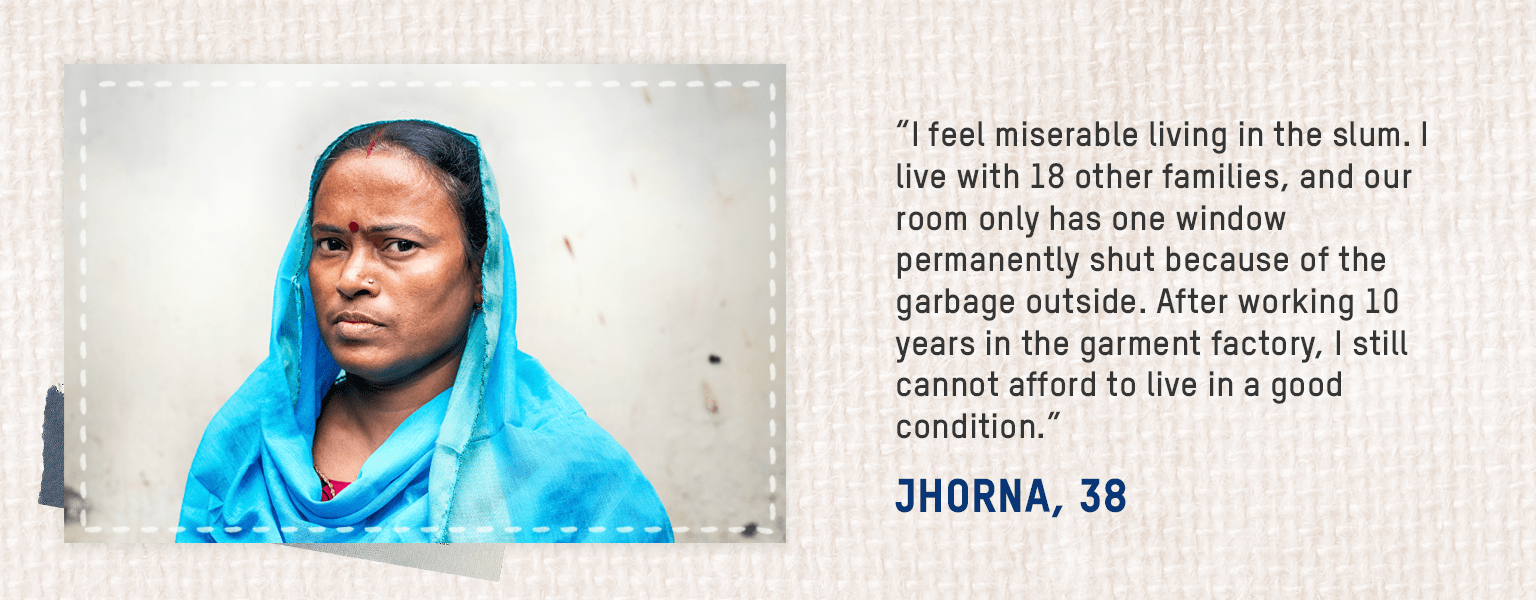

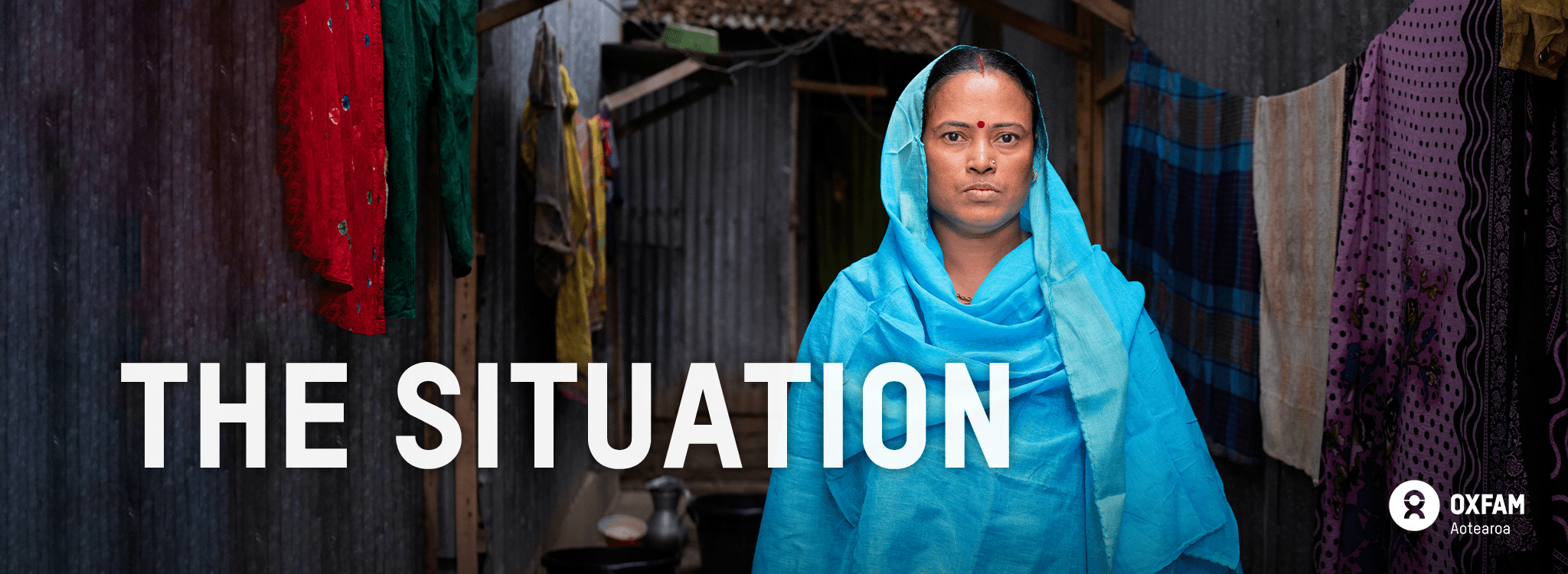

Out of the 75 million women garment workers around the world, only 2% are paid a living wage. The vast majority of women earn poverty wages despite working long hours – up to six days a week, twelve hours a day. Most have to choose between feeding their families or having a dry, safe home.

But we know that a better life is possible for the women who make our clothes. The problem is that companies like Kathmandu, Glassons, Macpac, Hallenstein Bros, Lululemon and H&M allow poverty wages to be paid to the women who make the clothes they make millions off. But they can take responsibility. Other companies such as Cotton On, Country Road and Gorman have taken responsibility – we asked them to make a commitment to do better, and they did. Together, we can get all the companies that sell clothes in New Zealand to do the same.

Across the world, people like you are standing up for the women who make our clothes, demanding that they are paid a living wage. More than 150,000 people have pledged to stand with the women who make our clothes and demand a life of dignity for them.

You can join them.

There is no good reason why women and their families have to choose between rent or food. There are no good reasons companies pay these women less than enough for a dignified life.

Together, we have the power to get the women who make our clothes a living wage, so they have enough to live in a decent home, provide for their loved ones, and watch their children flourish.

The basics

Fashion companies earn billions in profits every year, thanks to the women who make the clothes they sell. We know that the cost of paying a living wage can be easily absorbed by these companies.

We would like you to join us and the women who make our clothes by demanding that brands uphold human rights and pay a living wage. We’re starting with 6 well-known brands in New Zealand: Kathmandu, Macpac, Glassons, Hallenstein Bros, lululemon and H&M. These companies have more than enough capacity to ensure living wages are paid to these women.

Oxfam doesn’t believe the cost of a living wage should be put on consumers. These brands make enough profit to pay a living wage. They can afford it without transferring the responsibility to the customers.

Oxfam does not advocate for boycotts, as this may result in workers losing their jobs. The garment industry is an important part of the economy in many low-income countries, and we want this to remain the case.

Instead, we want to see changes in how brands currently do business. We want them to make sure they do not exploit workers by allowing poverty wages to be paid to make their clothes.

We want people to earn enough so they can put food on their table and live decently, together with their families. We urge you to use your power as a consumer and tell companies that you care about the workers who produce their clothing and ask them to pay a living wage.

The campaign calls on all brands to ensure that the workers making their clothes are paid a living wage. As a start, we are working to influence six brands who could model the journey for other New Zealand brands to follow. We have chosen well-known, high-revenue, and public companies selling their clothes here in Aotearoa. By working with the best-known brands here in New Zealand, we encourage a “race to the top” on wages for the women who make our clothes. We look forward to engaging more companies in the future.

Absolutely! Our policy asks are aligned with many international legal instruments and standards, including:

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights

- International Labour Organisation conventions

- United Nations Guiding Principle on Business and Human Rights

- OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains in the Garment and Footwear Sector

- Fair Labour Association Workplace Code of Conduct

- Transparency Pledge

- Clean Clothes Campaign

You can learn more about the garment industry and the women who make our clothes by checking out our Resources page.

Living wage vs minimum wage

A living wage is not a luxury but rather a minimum amount that all working people need to escape poverty. It is a basic human right that affords workers to live with dignity.

A living wage needs to be earned in a standard work week (no more than 48 hours) and covers a decent standard of living for the worker and their family.

A decent standard of living includes food, water, housing, energy, healthcare, clothing, childcare, education and transportation. It also includes some savings that can be put aside for unexpected events, such as a global pandemic.

The importance of paying a living wage to the women who make our clothes is now more critical than ever. With the compounding impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, climate crisis, and skyrocketing cost of living prices, it is high time that brands ensure that living wages are paid to the women they make millions off. Brands have the power and responsibility to make sure their workers are paid enough not just to survive, but thrive.

There are various ways to estimate the living wage for a specific place, but the two key methods most relevant to the garment supply chain are the Anker Methodology and the Asia Floor Wage. Both provide a clear pathway for businesses to move forward on living wages. Both calculation methods are credible, with the Asia Floor Wage usually providing slightly higher figures due to differences in detail, approach and calculation.

The difference between Asia Floor Wage and Anker is due to the difference in assumptions and methodology. For example, Asia Floor Wage is based on a standard 3,000 calorie intake per day, a family size of two adults and two children, and one wage earner. On the other hand, Anker uses country or area-specific data and demographics to determine the calorie requirements, family size and the number of earning members in a family.

Whichever method companies use, there are some fundamentals that all methods have in common.

A living wage is the amount required to cover a decent standard of living for a worker and their family.

Originally, setting minimum wages in law was meant to ensure that workers were always paid fairly for their work – so that wages were enough for living healthily and in decent accommodation. In reality, many governments have entered a ‘race to the bottom’ on wages, trying to attract foreign companies by lowering wage levels and keeping them low. The result in many countries, including the key garment-producing countries of Asia, is that legal minimum wages are as low as a quarter of living wage.

All human rights are equally important: no one should have to work in an unsafe workplace or put their health at risk to earn money, and everyone has the right to fair pay for a fair day’s work. We believe focusing on a living wage is a crucial step toward protecting and empowering workers. This campaign helps to increase the bargaining power of workers and establish more long-term relationships in apparel supply chains, both of which would likely also lead to improved workplace safety and health.

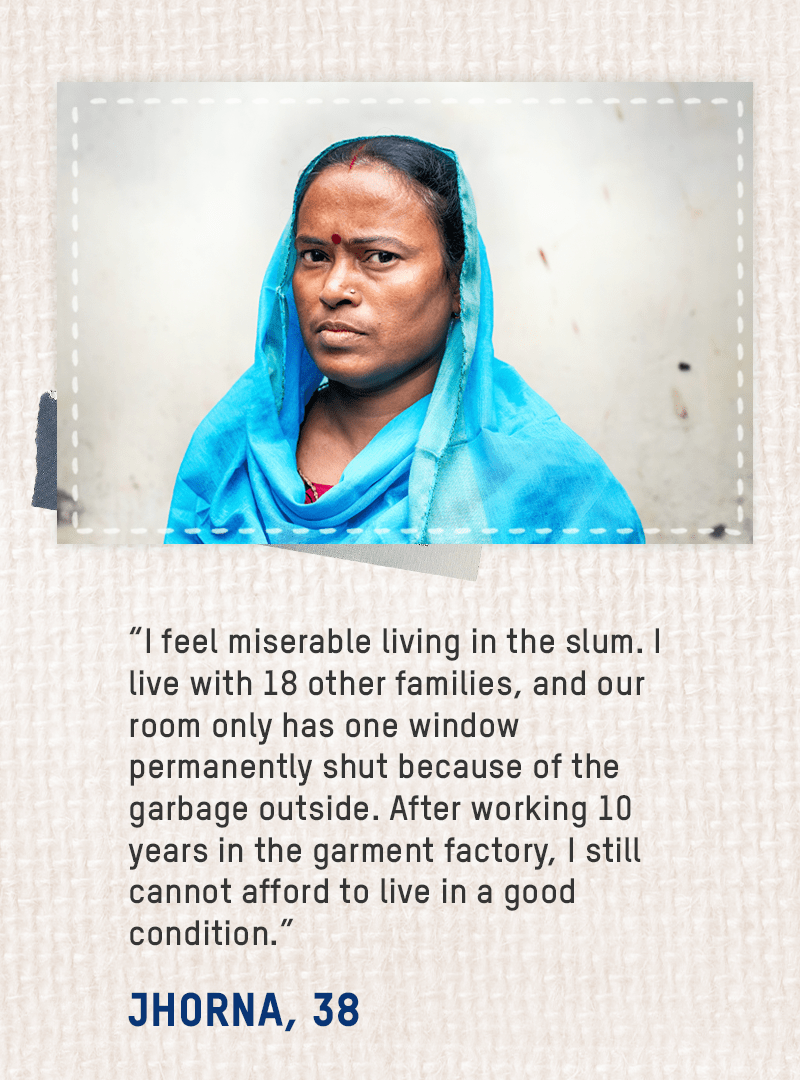

The Global Living Wage Coalition calculated that the living wage for Dhaka, Bangladesh is $361 per month. With the Asia Floor Wage calculation, it’s about $903. The existing monthly minimum wage is $136. The reality is that current wages in Bangladesh mean that even when the women who make our clothes work six days a week, up to 12 hours a day, they are still living in slums and consistently running out of food for themselves and their families. These wages push workers and families into debt and cause young women to sleep on concrete floors because a mattress is an out-of-reach luxury, and mothers are forced to be separated from their children for months at a time because they cannot afford childcare. This needs to change.

Oxfam thinks we can shoot higher and fight for human rights.

It is practically impossible for the women who make our clothes to live decently on what they’re making. Poverty forces them to live in slums, away from their families, working 12 hours a day and falling into spiralling debt. No one has the right to take advantage of women in poverty and violate their basic human rights in the name of profit.

Globally, the garment sector is among the largest employers of women workers. The sector holds great power and potential to impact the lives of millions of women in low-income countries and, by extension, their families and communities.

Making change together

If we can get even one or two major fashion brands to work towards a living wage in their supply chains, it will have a huge impact and improve the lives of hundreds of thousands of women and their families.

Right now, the women making our clothes often work up to 12 hours per day, plus extra overtime, but are paid as little as 65 cents an hour. That means they don’t have enough money for decent housing, food or health care – let alone any savings. That’s why we are working to change this.

There are many ways to hold brands accountable, and there is a role for everyone in that process. As a consumer, you can let brands know you care about the people who make your clothes and that you want to know their full supply chain. Message them on social media, ask the staff at a store you’re shopping at, email brands or ask in a website chat box – hey, you could even write a letter! The purpose is to let brands know that you care about who makes your clothes and that they receive a living wage.

Brands buy the clothing that is assembled in overseas factories. These brands have the option to change factories at any time and there is no shortage of factories willing to supply products to them. In such a market dynamic, buyers hold strong influencing power over the supply chain. If a brand makes it clear that it will only buy clothes from factories paying a living wage, the impact could be incredible. Brand power to effect positive change is stronger when they collaborate with each other and join multi-stakeholder initiatives.

Yes, and we will continue to do so. We have contacted each of the brands we are currently focusing on and communicated the need to commit to a living wage in their supply chains. Ongoing corporate engagement, backed by your voice, is how we aim to achieve a living wage for the women who make our clothes.

Poverty wages in the fashion industry is a global issue. Oxfam has focused our campaign on supplier countries where wages are the lowest and people are working long hours, but remain trapped in poverty. While most of the stories that you see here are from Bangladesh, our campaign focuses on paying a living wage to women who make our clothes everywhere. Garment workers in Cambodia, Vietnam and India face the same challenges as those in Bangladesh. The systemic exploitation of women who make our clothes is not just a problem in Bangladesh, but everywhere.

The garment industry employs far more women than men. More than 70% of garment workers in China are women. In Bangladesh, the share is 80%, and in Cambodia, it’s as high as 90%.

Women garment workers are an especially vulnerable group: they are poor, sometimes illiterate and many began working as children, so they lack education. Single women in these societies face further discrimination and marginalisation, making it difficult to secure their rights. Women garment workers have few support systems and endure harassment and abuse from managers.

While it’s not just women who are affected by these human rights violations, women workers tend to be more vulnerable to these risks than men. That is why we’ve put women at the heart of this campaign.

How about in New Zealand?

Yes, it is. While the Living Wage Movement Aotearoa NZ and the What She Makes Campaign are both parts of the global movement for a living wage for all, the two campaigns are separate entities in New Zealand.

The Living Wage Movement Aotearoa NZ focuses on New Zealand businesses and organisations and calls on payment of a living wage to workers here in New Zealand. Businesses and organisations can get accreditation from the Living Wage Movement Aotearoa NZ. They have their own requirements and processes.

The What She Makes campaign focuses on improving the policies and business operations that affect women who make our clothes in overseas factories.

No. The What She Makes campaign focuses on women overseas who do not earn enough to live with dignity. Oxfam supports a living wage for all workers everywhere.