Oxfam’s new report, ‘The Inequality Virus’, reveals that the wealth of the ten richest men has increased by half a trillion dollars since the pandemic began – more than enough to pay for a vaccine for all and prevent anyone on Earth from falling into poverty because of the virus. We have received lots of great questions about the report − here’s our answer to the 10 most frequently asked questions.

How can you be sure that Covid-19 will lead to a huge surge in inequality across the globe?

The IMF, the World Bank, and the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development have all said raised concerns that we will see a COVID-fuelled spike in inequality in all countries across the globe.

These fears were echoed by a global survey of 295 economists from 79 countries, commissioned by Oxfam, where 87 percent of respondents said they expected an ‘increase’ or a ‘major increase’ in income inequality in their country as a result of the pandemic.

It is also echoed by what is happening on the ground in rich and poor countries alike. The richest in society have seen their savings increase during lockdown, but the poorest in our society have seen their incomes fall and often had to borrow to survive.

While it will be some time before we have the data that is needed to produce a concrete measure of inequality, everything points to an increase in inequality in every country for the first time since records began unless governments act now.

What is the link between wealth, inequality, and poverty?

Our deeply unfair economies are enriching an already wealthy minority at the expense of millions of poor people. Over the last 40 years the richest 1% of the global population have captured more of the proceeds of economic growth than the poorest half of humanity combined. This inequality fuels poverty.

If the proceeds of economic activity had been shared more evenly, if governments invested in healthcare and education rather than slashing the tax bills of wealthy individuals and corporations, if companies prioritised a living wage for workers over bumper pay outs for shareholders, if access to medicines and vaccines was prioritised over the intellectual property rights and profits of big Pharma, then poverty could have been eliminated many years ago.

Why did billionaire’s wealth rebound so quickly?

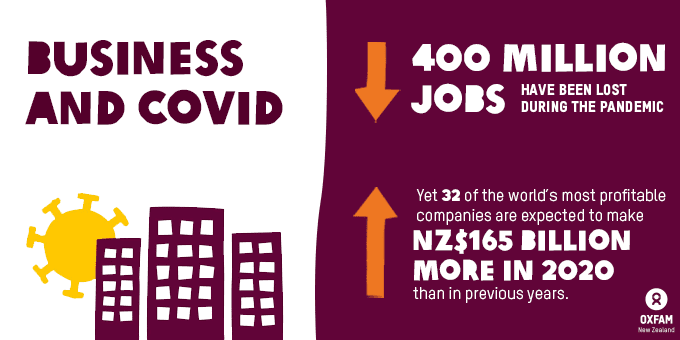

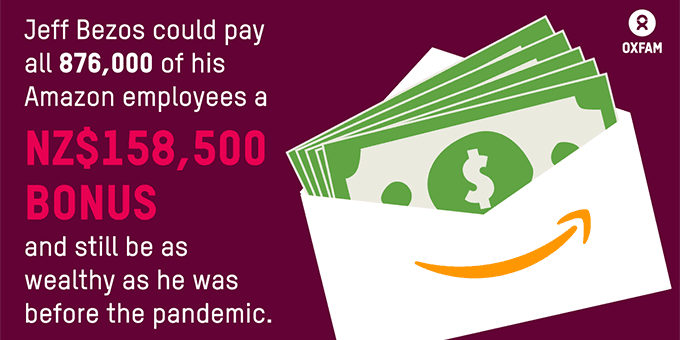

Stock markets suffered the worst shock in their history when the pandemic was announced, destroying billions of dollars’ worth of financial assets. Central banks such as the US Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank injected billions of dollars to prevent a crash, the markets quickly rallied, and with them the fortunes of the world’s richest people who hold much of their wealth in stocks and shares. As a result, billionaires recouped their COVID-19 losses in just nine months, yet it could take the world’s poorest people more than a decade to recover.

Why is Oxfam criticising billionaires and corporations for being successful and making a profit?

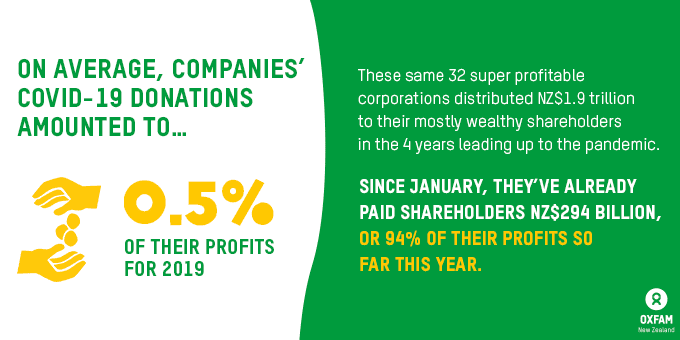

Making money is not the problem but excessive profits and extreme wealth are. These are the symptoms of a broken economic system which is benefiting a minority of people at the expense of everyone else.

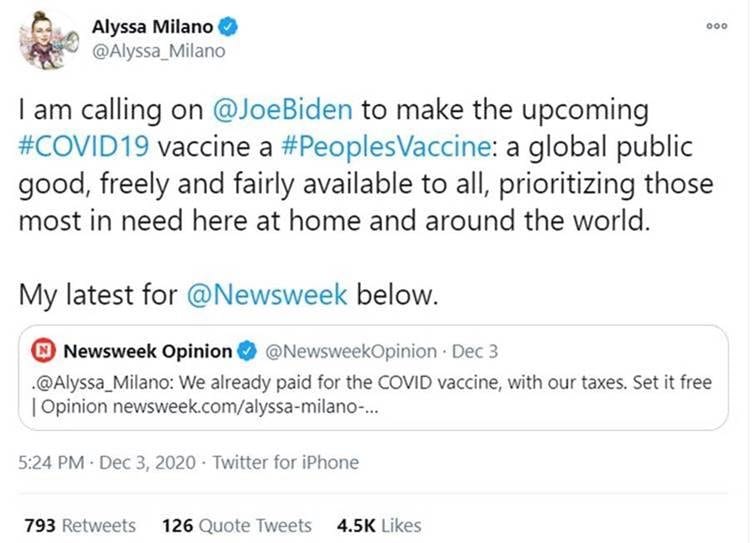

Take the pharmaceutical industry. The US government invested $1 billion of US taxpayers’ money in Moderna to support the development of a COVID-19 vaccine. Despite the fact the company only has the capacity to supply vaccines for less than 7% of the global population by the end of the year it is refusing to share technology and knowhow that would enable other manufacturers to produce it. Moderna has also pre-sold all the vaccines they will produce this year to rich nations for a high price, leaving nothing for developing countries. This has made the owners of Moderna very rich indeed. This is exactly the kind of economic failure that drives extreme inequality.

Why is Oxfam criticizing wealthy people such as Carlos Slim, Jeff Bezos, Mark Zuckerberg, have made multimillion-dollar donations to fund vaccine research, support hospitals, and help those who are suffering during the COVID-19 crisis.

People who use their money to help others should be congratulated. However charitable giving is no substitute for wealthy people and wealthy companies paying their fair share of tax, and it does not justify them using their power and connections to lobby for unfair advantages over others.

For example, US corporate philanthropy amounts to less than $20 billion a year but corporate tax dodging cost the US an estimated $135 billion in 2017.

Why is the pandemic hurting poorer people more than wealthy people?

In every country in the world the poorest people in society have been hardest hit by the pandemic, and especially women and people from marginalised racial and ethnic groups.

These people are more likely to work in sectors −such as retail and tourism − that have suffered big job losses as a result of the pandemic, and these jobs are largely in the informal sector, so they are less likely to have redundancy, savings, or unemployment benefit to fall back on if they do get laid off.

These people are less likely to have access to decent healthcare when they are ill. They are more likely to live in crowded accommodation or work in jobs − as cleaners, shop assistants and care workers −that put them at greater risk of contracting the virus, and they are more likely to suffer underlying health conditions that put them at greater risk of dying from it.

These are people like Jean Baptiste, a 44-year-old father of three and migrant worker at a meat processing plant in the US. The failure of the industry to implement proper safety measures has led to a series of COVID-19 outbreaks. When Jean became ill, he was told to continue working and hide his fever. When he died the company failed to inform his family or his co-workers. After his widow shared her story with the media, she received a card and just $100 in cash. Today she is struggling to support her children alone.

Which governments are handling the pandemic well, and which are handling it badly?

Governments’ catastrophic failure to tackle inequality means most countries were woefully ill-equipped to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Millions of people have died or been pushed into hunger and poverty because of decades of failure to invest in public healthcare, protect workers’ rights, or provide adequate financial support for people who can’t work. And while COVID-19 has been a wake-up call for some governments, others are still failing to act with disastrous consequences.

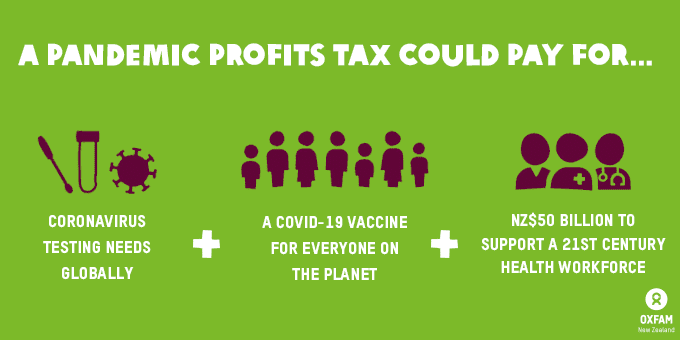

For example, the Kenyan government has responded to the COVID-19 crisis with tax cuts for the wealthiest and big business but has provided little additional funding for public health or to help people who have lost their income as a result of the crisis. By comparison, Argentina has introduced a temporary solidarity wealth tax that could generate over $3 billion to pay for thier COVID-19 response including medical supplies and relief for people living in poverty and small and medium-sized businesses.

How can governments afford to implement all the measures Oxfam is calling for in the middle of an unprecedented global recession?

Governments will need to invest to get economies up and running so the question is where should these investments be made? Oxfam is calling for governments to prioritize investments in areas that will deliver dignified, sustainable jobs, and not waste billions bailing out wealthy companies unless conditions are attached such as a requirement for the company to pay its fair share of tax or cut carbon pollution.

Building back fairer, greener economies will bring huge benefits for people and the planet. A study by Climate Action Network International found that investing in renewables in the US generates almost 3 times as many jobs as investing in fossil fuels, yet G20 nations had pledged $251 billion of COVID-19 recovery funds to fossil fuel companies as of November 2020.

Why is Oxfam calling for tax hikes at a time when tax cuts are needed to stimulate economic growth and job creation?

The idea that low taxes for the richest are good for economic growth and job creation is outdated. Gita Gopinath, the Chief Economist of the International Monetary Fund, recently came out in favour of one-off solidarity taxes on wealth and high incomes to help pay for the recovery, called on governments to introduce fairer tax systems, and warned against a return to austerity in the wake of the pandemic.

A strong economy depends on an educated and healthy workforce, good transport connections, a strong communications network, and the rule of law —all these things are paid for with our taxes. That is why it is essential that everyone in society pay their fair share.

Does Oxfam want to abolish billionaires?

Oxfam believes billionaires are a sign of broken economic system and that extreme wealth should be ended. We m believe the world would be a better place if there were a lot less billionaires and a lot more nurses.